by Steve Henkel

Several years ago, long after I had moved away from Short Hills, I found myself thinking about the old Racquets Club, where I had spent many a pleasant hour growing up in the 1940’s. The club was the place at which I learned to play tennis in the summer and squash in the winter, to perfect my pool and billiard shots in the airy, skylight-lit and palm-filled atrium, to learn the rudiments of badminton, bowling, ping-pong, and even ice skating, when in the winter the tennis courts were flooded whenever a lengthy deep freeze was expected. I learned the basic dance steps and some elements of politesse at Mrs. Chalif’s dancing classes, and probably learned many other useful things that have been permanently branded into my subconscious.

As a youth I didn’t love building design enough to make architecture my life’s work. Instead, after studying engineering, getting an MBA, and spending thirty years with big corporations in New York City, I’ve ended up as a freelance writer of books and articles about sailing and sailboats. But I’ve always liked looking at cleverly designed houses, and larger structures too, and the Racquets Club is near the top of my list of examples of good architecture. Until it burned to the ground in early 1978, the club had all the right features: Artfully concocted style, with just the right blend of timeless decoration and modern practicality — not too formal, but not too unassuming either. A design appropriate to its setting and pleasing to its neighbors. And best of all, a place eminently suited to its purpose: to provide its inhabitants with the opportunity to relax and enjoy their surroundings, and to indulge in leisure games.

While ruminating about all this, I thought: Wouldn’t it be fun to gather together all the materials on the now-vanished clubhouse and study them. An extensive search for the original architectural drawings was totally fruitless. But my desire became a sort of obsession, and I began doodling a floor plan of my own, from memory. One thing led to another, and soon I was reaching out to others, soliciting old photos and ideas on how things had looked, inside and out. Through the kindness of Lynne Ranieri at the Millburn-Short Hills Historical Society, plus some input from the management of the new Racquets Club and others, plus many photos from the historical society’s collection, I collected enough information to complete the drawings you see here. Still, the results of this search are not totally conclusive. If you, the reader, can add anything to this Racquets Club lore, please do, by writing to me using this form.

Above: A rare view of the original Music Hall before any additions. Note the window with a rosette design in the gable end. It replaced a clock originally installed there.

The Racquets Club story starts with Stewart Hartshorn, a successful window shade manufacturer, who in the 1870’s decided to invest some of his wealth by fulfilling a boyhood dream, to create an ideal village. He chose for his site almost 1,600 acres of almost totally undeveloped rolling farmland, a part of Millburn Township even then known as the short hills. For starters, Hartshorn wanted an architect with a fresh eye to design a Music Hall, intended to be a sort of anchor building to attract cultured residents to Hartshorn’s village — residents who would appreciate a skillfully designed edifice, where they could meet other like-minded people and make new and interesting friends, relax, and be entertained.

To design the Music Hall, Hartshorn chose a 25-year-old boy-wonder architect named Stanford White, who began work on the project in the fall of 1879. The finished structure was opened at the end of May 1880. White was the designated partner of McKim, Mead & White for the project — his first full design after joining the firm. When complete, the new Music Hall was acclaimd by one and all, and White soon went on to fame, fortune, and an early demise, shot to death in 1906 by a jealous husband named Harry Thaw. You can read E. L. Doctorow’s short novel, Ragtime (1974), and Triumvirate, McKim, Mead & White — Art, Architecture, Scandal, and Class in America’s Gilded Age, (2010) by Mosette Broderick, to get two angles on some of White’s various adventures. Unfortunately neither of these books mentions the Racquets Club. A third work, McKim, Mead & White (1983), by Leland Roth, gives the club a page or two.

In the early days — before the addition of squash courts, bowling alleys, kitchen, bar, etc. — the club, first called the Music Hall and then, by the mid-1880s, the Casino, was simply the social center for the fifty or so families living at the time in Short Hills. The building contained a 175-seat theater on the upper floor, where plays and concerts were performed and municipal meetings were sometimes held. The space beneath was called the basement and sometimes the reading room, but more properly was a lounge or reception room. It was variously used for Episcopal Church services (from 1882 until the Christ Church building was completed in 1884), for elementary school classes (also starting in 1882), and of course for lounging, reading, and socializing. Later it was rented to the Short Hills Club, until that organization built its own clubhouse further up in the hills in 1928. Squash courts and locker rooms were added in the 1920’s. The building was rented by Hartshorn Estate to the Community Center until 1934. Then it was merged into the Racquets Club. In 1946 the property was purchased from Hartshorn by the Racquets Club of Short Hills.

The original Music Hall was a barn-like structure, and like many barns, used the post-and beam method of construction. That design gave plenty of space, and to attain the height necessary for an auditorium able to accommodate an audience as large as 175 in comfort, the roof beams soared high overhead. Later all that unimpeded vertical space would come in handy, when club members decided to set up a badminton court. The ceiling beams were high enough so that, as I remember, they posed no interference with the flight of even the highest lob of a shuttlecock.

Below the auditorium was the Reading Room, later called the Lounge, where members could play cards, read, relax and generally enjoy life. The room was kept stocked with a good supply of “leading weekly and monthly periodicals,” according to an early issue of the Short Hills Item. True to its purpose, by the mid-1880’s the Music Hall was dubbed the Casino.

Below the auditorium was the Reading Room, later called the Lounge, where members could play cards, read, relax and generally enjoy life. The room was kept stocked with a good supply of “leading weekly and monthly periodicals,” according to an early issue of the Short Hills Item. True to its purpose, by the mid-1880’s the Music Hall was dubbed the Casino.

I don’t know when the tennis courts were built, but the Racquets Club had five of them by the time I started learning the game in 1940. They were arranged the way you see them above — if my memory isn’t too far off. Court #1 was always used for the club championships, which occurred once or twice a year. Kids like me were warned away from court #1, on the grounds that we might scuff up its pristine clay surface. If the courts weren’t too crowded, we beginners would usually use court #3, and otherwise were relegated to courts #4 and #5 — perhaps an early lesson in respecting one’s elders.

Between courts #3 and #4 was a gazebo built in rustic style, from natural logs. It had built-in benches for lolling around in the shade, and was the perfect place to be between sets in the summer heat. The practice backboard, on a rise above court #2, was where I spent a lot of time as a learner. I recently found a photo of me with my father and our family dog, Pal, taken in 1940 when I was six, standing in front of the club’s screened porch, probably getting a little instruction before I was sent off to practice against the backboard. When I was six, I didn’t understand the need for constant practice to become an excellent player of tennis — or for that matter, to excel in any pursuit. Unfortunately I didn’t truly understand that until much later in my existence. What a difference it might have made in my life!

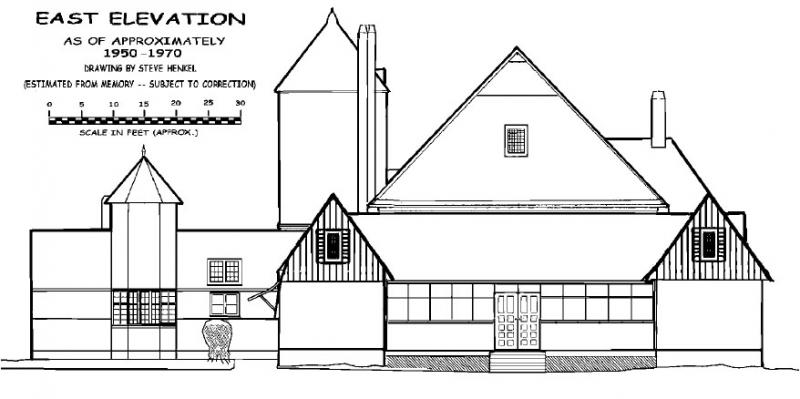

The floor plan of the first level was originally called the Reading Room but later its name evolved as other uses were discovered. Here we use Reception Room. The east wall of the original design ended just west of the sunken atrium, kitchen, and snack bar. These rooms, along with the bowling alleys, squash courts, mens’ and ladies’ locker rooms, living quarters for a club manager and his family, and a screened porch, were all added later. The so-called Palm Court was a sunken atrium with a glass roof, which had opening ventilation panels manually operated using a crank connected to a worm-driven gear system aloft. Potted palms and hanging plants adorned the room, which later was furnished with a pool table and ping pong table. Access to the Palm Court was through multiple French doors. The South Elevation shows the barn-like Music Hall on the left. It served several purposes, including recital hall, theater for dramatic productions, and town hall, among others. The bar and kitchen are at center, and the tennis and squash facilities and locker rooms are on the right.

The upper floor plan centers around the original auditorium and stage. My memories of Short Hills in the 1940’s include Mrs. Chalif’s dancing classes (as written in my earlier reminiscence in the Thistle for Fall 2001). Mrs. Chalif (nee Margaret Montgomery) and Mrs. Wells (wife of Henry C. Wells of Summit) ran classes that took place mainly on the ballroom floor, though refreshments (fruit punch and cookies?) as I recall were doled out downstairs in the reception room. Built-in seats along the north and south walls of the auditorium accommodated boys on one side and girls on the other. The arrangement was perfect for the method Mrs. Chalif used for pairing off boys with girls. If I recall correctly, she blew a whistle, and the boys who knew their targets rose quickly from their seats and sprinted toward the girls’ side of the room. Some of the girls, through pre-arrangement with their boyfriends, also got up quickly and started north towards their one-and-onlys. Inevitably the shy wallflowers and those who had failed to plan ahead — both the boys and the girls — were abandoned to make the best of what was left. Usually I was one of those leftovers. The lesson here should have been, “Think Ahead.” Louis Chalif (pronounced “sha-LEAF”), Mrs. Chalif’s father-in-law, was a Russian ballet dancer who immigrated to New York and ran a successful dance school in Manhattan starting in 1916. According to an article in the New York Times, he taught “interpretive, aesthetic, racial, ballroom dancing.” He was an outspoken gent, and reportedly once said that dance in the United States was often just a “cannibalistic orgy.” As a male wallflower, I couldn’t agree with him more.

Two views of the club from the south, probably taken in the 1970s. The design of the round tower, with the club’s main entrance under a wide arch to the left, greatly resembles the Newport Casino in Rhode Island, designed by McKim, Mead & White at about the same time.

The round tower is the central image most old timers mention when asked to describe the Racquets Club exterior. In the photo to left and above, a thick coating of ivy surrounds the lower, masonry covered part of the tower — a growth which alternately came and went over the years. In this view, incidently, it is easy to see that the tower is not exactly round, but almost U-shaped. A closeup photo, left below, resembles a giant fish with prominent scales. Those who believe in astrology might observe that Stanford White, who designed the tower, was born on the ninth of November, making him a Scorpio, one of the Water Signs.

It would be even better, they might say, if he were born between February 20 and March 20, the dates for a Pisces (“the two-headed Fish”) and also a Water Sign. Did White’s birth date influence his designs? Well… who knows! The critics seem to be split on whether White’s tower is a good design element or a bad one. One comment questioned the design of a round tower capped by a square roof, seemingly to no good purpose. The view shown here encourages the theory that the (partly) squared off cap does serve a purpose, namely to permit an inconspicuous opening for ventilation, to keep the air cool in the stairwell within the tower.

It would be even better, they might say, if he were born between February 20 and March 20, the dates for a Pisces (“the two-headed Fish”) and also a Water Sign. Did White’s birth date influence his designs? Well… who knows! The critics seem to be split on whether White’s tower is a good design element or a bad one. One comment questioned the design of a round tower capped by a square roof, seemingly to no good purpose. The view shown here encourages the theory that the (partly) squared off cap does serve a purpose, namely to permit an inconspicuous opening for ventilation, to keep the air cool in the stairwell within the tower.

Changes to the club’s facade included the loss of the rosette window, which lit the attic over the auditorium, and the big window below it, whose light at times disturbed the badminton players.

View from the tennis court side of the Club shows the entrance to the locker rooms and squash courts. The back side of the Club, parallel to Hobart Avenue, contained bowling alleys and manager’s quarters.

During the 98 years of the old Racquets Club’s existence, many events occurred, some perhaps leaving a residue of tales as yet untold, of ghosts who may still haunt the space once formed by bricks and mortar. Children (and maybe some adults?) were known to explore under the original stage, which was raised at the back — upstage — so the audience could catch the action from chairs on a level floor. Other children (and maybe some adults?) have ventured to the rafters above the stage, and into the attic and the cellar to explore. What wonderful secrets might yet be discovered? What nasty demons exorcised? Perhaps only time, and latent memories so far hidden from us all, will tell.

* * *

Both Steve Henkel and his wife, the former Carol Pippitt, grew up in Short Hills. Both graduated from Millburn High School, Steve in 1951 and Carol a year later. Steve lived at 386 White Oak Ridge Road (though in 1952 his parents built a new house at 272 Hartshorn Drive). The house at 386 White Oak Ridge Road was converted to the Wee Folk Nursery School, and the house at 272 Hartshorn Drive was torn down to build a new, bigger structure with a Roberts Drive address. Carol’s house, at 100 South Terrace, was still intact in 2012. After college and until moving to Darien, Connecticut in 1961, they lived at 68 Hemlock Road, then a small garage apartment behind the Carrington mansion on Hobart, but now a much larger private residence.

386 White Oak Ridge Road 272 Hartshorn Drive

100 South Terrace 68 Hemlock Road