Interview November 25, 1979 with John G. Dow, Joy Wheeler Dow Jr., Mrs. John Dow, Diantha Dow Schull and Thomas Dow. Elizabeth Howe and Frances Land of the Millburn Historical Society were present at the interview, then accompanied the Dow family on a tour of the houses done by Mr. Dow in Millburn and one in Short Hills.

“I’m Joy Wheeler Dow Jr. and I’d like to introduce one of my father’s other children who is Congressman John G. Dow and he is now going to take the floor. In other words, I am recognized, is that right?”

J. W. Dow, Jr.: “Well, yes.”

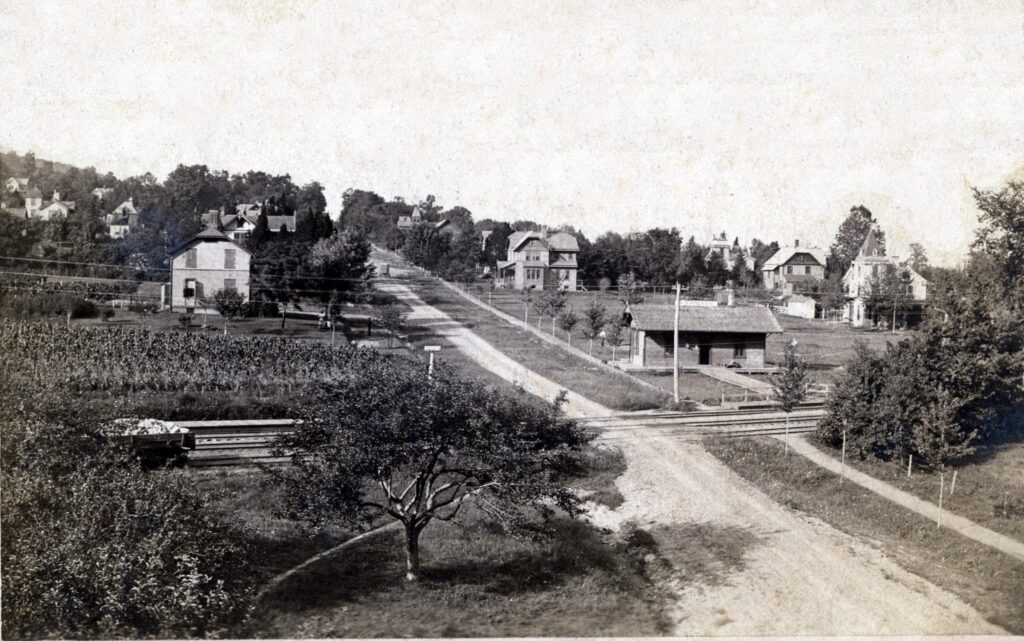

John Dow.”My father was born in 1860 in New York City. He was the son of Augustus Francisco Dow and Sarah Benden Dow. His father was a very successful spice merchant in New York and lived on Bank Street, #25 I believe. He died in 1864 when my father was four years old, and a good deal of the family fortune vanished in the few years for various reasons. My father and his mother and his sister, who later moved to Wyoming, moved to Brooklyn, and they lived there until 1880 or 1882. Then they came out to Wyoming which was then one of the newly-opened commuter communities on the Lackawanna, and they lived in a house in Wyoming which they called “Rose Cottage.” It was a little old wooden Victorian house which may still be there.” (Rose Cottage is at 78 Chestnut St.)

Howe: “It is.”

John Dow: “Oh, good, I’m glad to hear it’s there because I wanted to show my children. Anyhow, my father was at that time a clerk in the New York Mining Exchange, and he worked as a secretary to the famous financier Pete Sweeney, who belonged to the…”(lost on tape)

Diantha Schull: “There was no family connection that brought them to New Jersey?”

(Page two)

John Dow: “No, there was no family connection that induced them to move out here. I suppose that it was one of the newly-opened and most accessible of the commuting areas, and the cottage they located in was near the railroad station–the Millburn railroad station(then on the corner of Wyoming and Glen). And anyhow, my father was a clerk serving Pete Sweeney, who belonged to that ring of notorious financiers and he was not particularly good at business, but he was interested in architecture. My father had no more education than the eighth grade. He had been through the grammar school in Brooklyn, and that was all the education that he had except for studying a little bit at Cooper Union in New York City. And it was very remarkable that he had learned all the several orders of architecture that are manifest in the houses here in Wyoming and in Summit: the Early American, the very early Colonial, the Georgian types, the Tudor style, the Jacobean, and so on and he was able to render those orders into the various homes in this area. He was not an innovator like Frank Lloyd Wright, but was probably as good as anybody at accurate–and we’ll say pure–renditions of the houses, of the architecture, of the styles. A great deal of American suburban architecture has elements and themes from traditional architecture but none of it was rendered probably as accurately to the old traditions as these houses that my father drew. At least, we like to think so in the family.

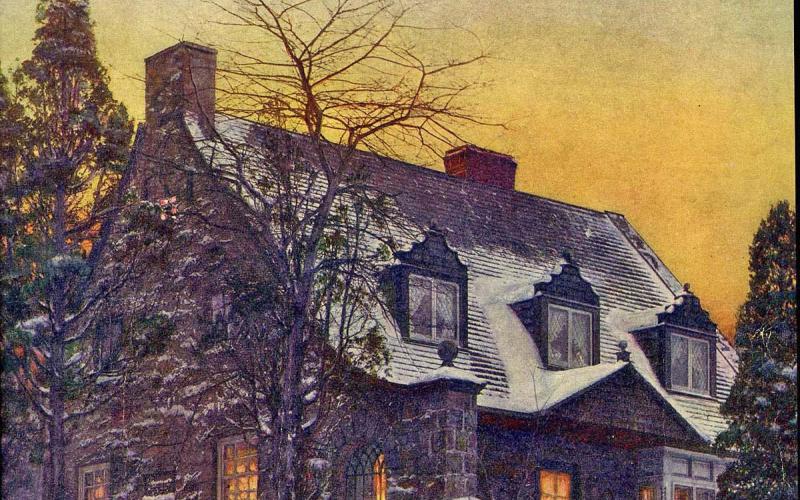

Well, my father did have a little money left over from his father’s estate and he being interested in architecture and hoping to branch into it, built a house across the street (actually behind the lots on Chestnut) from Rose Cottage, which the family called “Greylingham.”

(Page three)

It was a habit in the family, or in my father1s way of doing things– he was trying to create a climate ‘or spirit in this architecture by erecting a building. But it was also trying to memorialize a way of living, and therefore, he gave names to the houses somewhat in the fashion that we know that the English gave names to their houses. And therefore, he invented the name Greylingham which might have come out of some place in England, and he built a house there which was not really completely true to any particular form but which was a good substantial house with interesting features. Then I believe he sold that or if he didn’t sell that he managed to build a house next to that which is called Princessgate, which is a rather Georgian type house, rather a cozy house where he lived. I might say that my family moved from Rose Cottage to Greylingham, and then when he sold that he moved to Princessgate, and when he sold that they moved on. And this way he was able to finance the houses and go onto something better. And in each case he was very enthusiastically involved and deeply committed in an emotional way to the next house, because each one was different and each one was a new venture for him.

About that time, my mother’s family, their name was Goodchild, and my grandfather John Goodchild, was a stock broker in the Stock Exchange in New York. He was the specialst for the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul stock, a railroad that nearly shut down two weeks ago. Anyhow, he brought his family out here. It consisted of three daughters and a son, and one of the three daughters was none other than my mother, Elizabeth. And after a while, he married Elizabeth Goodchild.

Now in the time that he was there in Wyoming, he belonged

(Page four)

to what we then called the social goings on of the community and they had many plays. He was involved in plays—in writing plays, in taking established plays and putting them on. And he was part of the theatrical society there. And they had a good deal of fun I guess. Anyhow, early in this century he married my mother, and the one special link here was the fact that he was hired by John Goodchild to build another house, which my father leapt at. He took that opportunity.”

Howe: “Do you know where the Goodchilds lived in New York?”

John Dow: “Oh yes, they lived in upper Manhattan on Lenox Ave.”

Howe: “But did they own a house in Wyoming before this?”

John Dow: “No, they came out like my father. They were newcomers. This was a time when the suburbs were blossoming. Heretofore without railroads that could carry commuters to New York it was still farm country, but once the fast trains came into being, then the place simply mushroomed. My grandfather was another who followed the crowds so to speak and came out here with his family. My mother and her two sisters and brother all came then and my father designed a house for my grandfather John Goodchild which was called Eastover. And that is one of the more impressive houses that he built. It was an oval dining room. And then he built some other houses in the area. He built one for the Calloway family which is up above the Eastover house. The Calloways, I believe, were involved in investments in New York. I remember Mr. Calloway. When I was a little boy he used to give us quarters, which was quite a lot in those days.

Then after my father married my mother in 1904–I was born in 1905 by the way–they built what is known as the Rabbit House which is a couple of blocks away. And that’s where I arrived after I was born, and my brother

(Page five)

Colonel Dow, he was born while we lived in that house. He was born in the Norton Hospital in South Orange. He was the first baby born in the Norton Hospital, but now we understand that it’s out of date and that’s the end of that.

I remember as a boy living in the Rabbit House.”

Joy Dow, Jr: “I remember it also.”

John Dow: “It was a very elegant house. Again you see my father attached names to all these houses, because he was more sentimental than he was technical. And he liked to reproduce the character of the house in the period, and add sentimental names and so on. He was quite a character, really. Very unique at that period. He was not an engineer, and I don’t believe that he could figure a stress for a roof, because he had not had that training. He had picked up a certain amount, I guess, by rule of thumb. But he never did put up great engineering edifices, or anything like that. So he confined himself pretty much to what we call middle class, upper middle class homes.

Now he was almost the first architect who introduced traditional values for small middle class homes–for the average American, who up to that time not having much money, just lived in boxlike structures of which there are plenty down here between here and New York City. While my father didn’t design the great Vanderbilt mansion, he did try to apply the same quality of architecture to the small homes of people who were starting to rise up in the suburbs.”

Howe: “You don’t have any idea whether he had a favorite architect or carpenter he worked with?”

John Dow: “Not–a carpenter. I was telling them up in Summit, where we went this morning, that the carpenter…that a carpenter by the name of Wahl was the one who built the staircase and the mantelpiece on that house in Summit.

Howe: “What is the address of that house?”

(Page six)

John Dow: It’s on Belleville Ave. It’s a very high house. It’s white, and it’s owned now by some people named Dorn(?), but I don’t know that Mr. Wahl had worked in any other of his houses. I wouldn’t know t hat.”

J. Dow Jr. “45 Belleville Ave.”

John Dow: “ My father may have had certain favorite carpenters or masons, but I don’t know the names.”

J. Dow Jr. “How about architects?”

John Dow: “Well he did his own.”

J. Dow Jr.: “But did he have any disciples? Mrs. Howe was suggesting that he might have had some.”

John Dow: “He had some young men who used to come out and visit us. One of them was a man named {Rossham or Haddam?), who came out and visited us in Summit, and this was prior to World War I and he went to war and we never heard from him again.

J. Dow Jr.: “Amar Embry and I were good friends and corresponded.

John Dow: He was a good friend of Amar Embry who was a publisher of architectural publications. He admired an architect whose name I don1t recall very well in Annapolis, Maryland. It began with an H.”

(Questions about Will Bradley)

John Dow: “No, let’s face it, my father didn’t have a college background, he had not worked in an architectural office, he didn’t have the connections in the business so to speak, he didn’t have the professional ‘in’–if you want to call it that. He was a loner. Very much of an individual, and a lot of the architects were more conventional than he. He didn’t know how to circulate in those rare circles, he didn’t know how–to put it very bluntly–to hack it with the boys. He wasn’t temperamentally suited for that

(Page seven)

and this was in a sense a great drawback, because he was poor all his life. Made very little money from his business. Awfully poor. Uncle Joy and I can tell you some stories about that.”

J. Dow Jr.: “Poverty isn’t ugly, I want to tell you. That’s a new idea. We had a lovely childhood.”

Howe: “But you would never gather that from any of his writings and the places where they have been published.”

John Dow: “Well, I don’t mean to say we didn’t have roast beef on the table, but we had plenty to eat.”

J. Dow Jr.: “I never tasted a steak in all my boyhood.”

Mrs. John Dow: “You would have to say that he was a highly-educated man–a self educated man.”

John Dow: “But he just didn’t have the knack of getting along. That’s why, I suppose, he doesn’t have, or I can’t recall. any other architectural people he was close to. But he did, he was able to write articles about his houses. His houses were sufficiently distinctive so that the magazines would publish them. And every house he did was written up, maybe two or three or four times.”

Howe: “We have been using some of the citations. We were really pleased to find so many articles.”

John Dow: “He wrote for House Beautiful, the Architectural Forum, House and Garden. Modern Priscilla was one he did, and the White Pine series.” J. Dow Jr.: “Mrs. Howe, he had every artistic talent almost known to man, except he couldn’t sing. He could speak beautifully and his handwriting was magnificent. He could copy a Rembrandt so you couldn’t know which was which, he played Chopin, he wrote, he designed, and he was completely preoccupied with this.

(Page eight)

Nothing else existed. He was a wild eccentric. He had no friends, he had no time for friends. Everyone liked father, but he had no time for those indulgences. Until he was 77 he was up at six and he would brew that lapsang souchong tea. I’d smell it downstairs. He could still afford that and he would be up and at it at the typewriter, typing something, such as a letter to the New York Times or some damn thing.”

John Dow: “He wrote many letters to the New York Times when he was crotchety.”

J. Dow Jr.: “Jack can correct me, but he had a perfectly good name–Joseph Augustus-—a man’s name which I would have loved (“Joseph Wheeler,” according to John)–which he changed to Joy Wheeler at the age of twenty-one.

Land: “Why did he change it, do you know?”

John Dow: “Well, maybe because he liked things that were elegant.”

Mrs. John Dow: “…in his travels he had studied the houses, especially the English houses, in such detail, and he tried many of those elements in these houses which we have seen.”

Diantha Schull: “When did he travel?”

John Dow: “He went to Europe at least twice; I think three times. Once on his wedding trip; and once or twice before. Wherever he went, he took pictures. He had one of those big cameras on a tripod. We still have it.”

J. Dow, Jr.: “He was a great photographer. Done on glass plates.”

John Dow: “We have several boxes, and I am sure there might be some of these houses on them. All the pictures in those magazines such as the one you have are the ones he took.

(Page nine)

Howe: “One of the things I mentioned to you was that one of the owners went to England to try to find the prototype for their house only to discover that it had been destroyed during World War II. That was Canterbury Keyes.”

John Dow: “Yes, I didn’t mention that. There are some others. He built a house down the street from Wyoming Ave, almost in Maplewood, but I have no idea where that is.”

Howe: “Well, I think I can find it. There’s one I would like some verification on. A house on Linden Street, next to the Tennis Courts, and it looks like a pub inside, with a cathedral-type ceiling and you go down a couple of steps into this room. They have a beautiful bay window with stained glass, and I can’t believe that it’s not one of his houses.”

John Dow: “Well, I doubt if it is. I’m more than willing to look at it. The only house on Linden Street that he built was my aunt’s (Ada). That little one. Ada was his sister.”

Howe: “She had a companion, Miss Swift, and she died two or three years ago.”

John Dow: “Well, she was a hundred and three or five. I used to go and see her occasionally. She died in an Episcopal Home in Hackettstown. She was a lovely person.

Howe: “Apparently, she was corresponding with people up to three years ago.”

John Dow: “Well, it might be. My aunt was somewhat like my father–rather a positive character. They used to say Miss Swift was like a tender to my aunt’s locomotive. She was a sweet woman, and I used to drive down on my bicycle, from Summit, and cut my Aunt’s grass on Linden Street. Her cottage says ‘Mein genugen.’

(Page ten)

(John Dow, cont’d) I wonder if we have mentioned all the houses.”

Howe: “And then there is the cottage on Wyoming, and there is one up further on Wyoming–on the map it’s called Lynn Tepper Regis, which is one of his later houses, quite a large house.”

John Dow: “You know I’m vague on that, I don’t remember it very well, but I don’t say it wasn’t so.”

Land: “What about the one next to the Hobart Avenue School? It’s in the American Renaissance (a side view) and it’s a dead ringer for it.”

(The Dows did not know of this one, will look.)

Howe:”What about the one over in New Providence?”

John Dow: “Oh, the Red Riding Hood Cottage. I was going to take them out there, but I thought we’d be late here so we didn’t go. Well, that we did–well, let’s go on. Then we moved to Summit in 1910. We lived there ten years, then he did this again and sold his house and built a new one in New Providence. We were there a little bit and by that time, he was getting on and he decided to take off for New England. I guess he wanted to retire. I think he felt the people in New England would have a greater appreciation for his work.

The real reason he didn’t make money was that people didn’t appreciate his work. It was only occasionally that they did. Most of them thought that he was fancy and therefore not practical, and in that generation people weren’t interested in this type of thing.”

J. Dow Jr.: “And he was unbending, Mrs. Howe. We would say, “Father put the window out of the chimney, but get the job.” He would walk up and down the living room and beat his breast and say I’m Joy Wheeler Dow and I won’t compromise my art.”

John Dow: “His brother used to get after him and say, “Joy put the chimney out of the window.” But this was one of the reasons he didn’t succeed.”

(Page eleven)

Diantha Schull: “You mean you actually remember him losing commissions because of this?”

John Dow: “Well, I remember him submitting plans, not too often, to people who didn’t accept them. Well, you know, what he needed was a business manager. I think some of the great architectural firms like McKim, Meade and White and Cram, Goodhue and Ferguson who were contemporaries of my father, they used to say that one man was the salesman and the other was the artist. And he was the artist, but he didn’t have a partner to go out and get business.”

Howe: “Did he do any houses in Michigan?”

John Dow: “Yes, two. One in Detroit and one in Marquette. Both of them were pretty good.

Howe: “Were they people who lived in this area?”

John Dow: “No, they read of him in the magazines. The one he did in Detroit was for Dr. Went. The one he did in Marquette was done for (couldn’t remember), but they are written up. He did one in Illinois. That one is rather vague in my mind. I think all three of them were done later. They wouldn’t be in the same period as these. They were written up. They were good houses. Very distinguished houses.”Diantha Schull: “How do you account for the fact that he was able to get so much publicity in architectural magazines.”

John Dow: “Well, he did know Amar Embry. He did have an acquaintance with the publishers. Also in that period there weren’t too many architects producing very distinguished stuff. They were just putting up the old conventional homes. There weren’t many who could say “Look at this, this is special for this, this, and this reason.

(Page twelve)

And there weren’t too many who could do that.”

Mrs. John Dow: “Also, didn’t the different architectural magazines have competitions which he entered?”

John Dow: “Occasionally. I remember when I was a boy his taking me into the architectural exhibits at the American Architectural Association, and he won some things there.”

Land: “Was this the New Jersey Society?”

John Dow: “No, this was the national. He did belong at various times to the New Jersey Society of Architects, but being so poor, he couldn’t pay the dues most of the time. And he fell out, and there was a man named Roberts who was somewhat friendly and was the secretary or the executive director who used to prod him to join. He even said he could be a member without paying dues. It was touch and go.”

Diantha Schull: “That Will Bradley she referred to, you don’t have any recollection of his knowing him?”

John Dow: “The name is slightly familiar.”

Howe: “David Gibson felt that there might have been some connection between the two–especially because of the interiors.”

Fran Land: “Bradley was very involved in the craft movement, and a lot of Mr. Dow’s interiors do bear some relationship to this.”

John Dow: “I just can’t say. I want to say that my memory is not perfect by any means. I was quite young really when my father was in his heyday so that he probably did do some houses but I can’t remember.”

Land: “Do you remember Mr. Hartshorn at all?”

John Dow: “No.”

Land: “I’m sure they must have met each other.”

(Page thirteen)

John Dow: “Oh, probably did. He knew who the architects were. He knew many of them.”

Land: “Mr. Layng?”

John Dow: “No. I remember one time when we lived in Summit and we were quite hard up, and one of the architects in the field got him a job at the Cunard building which is a big skyscaper downtown at the foot of Broadway in New York. He had to check the pipes and the piping. He hated it, but then that particular assignment ran out. I remember his coming back and saying that he had raised a question with the master plumber about something and the master plumber said, “You know, you’re right about that and I haven’t had anybody raise that question before.” So that he still had some abilities. He could understand construction and so forth, even though he didn’t have an engineering degree.”

Diantha Schull: “As far as materials go, was that typical that he try to get the very best materials?”

John Dow: “No, he wanted them because they were right. If he was building an English house and no laborer in this country could provide what be needed, and he knew it was manufactured in England, he would get it from England. He had some leaded windows.”

(Conversation followed, while looking over the survey book.)

(Group then took a tour of Wyoming and Short Hills.)